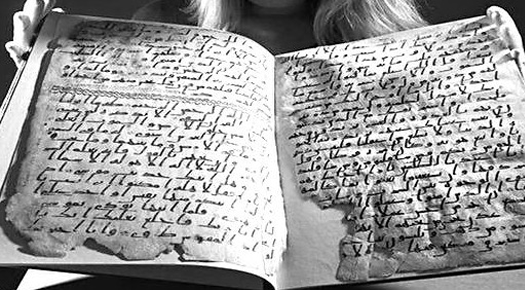

Fragments of the oldest Koran in the world were recently uncovered from within the collection of Cadbury Research Library at University of Birmingham. The two well-preserved leaves of parchment possibly date back to the time during which Prophet Mohammad was still alive, as radiocarbon analysis suggests that the documents were written in a rather elegant script between AD 568 and AD 645.

“We knew it was going to be a good date, but when we actually got the dates it was just an ‘Oh my goodness’ moment,” Susan Worrall, director of the special collections of the library, said. “You don’t get very many days like that in a career.”

The Prophet is believed to have lived between AD 570 and AD 632. During his lifetime, his teachings were shared orally or recorded partially in writing. But soon after his death, his followers collected all the texts that could be found so they would be able to compile them and abide by Mohammad’s teachings for generations to come.

Click to view video: https://youtu.be/MF4f1gsqFyM

Historians have suggested that the newly discovered texts are possibly part of the earliest writings that were eventually included in the Koran or belong to the first authorized version of the same that was written in AD 650. Unsurprisingly, the ancient text is almost identical to the Koran used by Muslims today but the parchment is so old that scholars are likely to reconsider the accepted date for the compilation of the text in question.

While the parchment made it to the library with a bulk of other ancient Middle Eastern manuscripts dating back to the 1920s, theologian, scholar and Chaldean priest Alphonse Mingana, who collected the documents, is unsure where he first found them. Interestingly though, both the parchment and the beautiful script inside it closely resemble other documents that were found inside Egypt’s oldest mosque in AD 642 but are currently housed at Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.

These leaves of parchment, which contain part of the suras (chapters 10 to 20), were possibly misplaced since they were bound together with another text that has similar handwriting but happened to be written 200 years later.

Alba Fedeli, a PhD student at the university, who has been working on Mingana’s ancient manuscripts, identified the two mismatched pages recently.

“We know her very well; she has been working away for some time on the Mingana collection. When she brought this to us and said she thought two leaves came from another manuscript, and we looked closely at them, we could see that she was right,” Worrall said. “At first glance they look identical to the other pages, but once you know you can see that the text does not flow. The script is wonderful, still legible to anyone who can read Arabic today.”

Worrall also said that the university had turned down a request a few years ago by a German institution that wanted to test the manuscript. However, after Fedeli made the important distinction between both texts, the university agreed to fund all the tests as well as sponsor the necessary conservation work. Even though the verses in the parchment are incomplete, it is believed they were an aide memoir for an imam who already knew the Koran by heart.

David Thomas, professor of Christianity and Islam, referred to the discovery as one of the most surprising secrets that the university’s collections have had to divulge. He said this parchment supports the notion that the version of the Koran used today has barely undergone any change from the earliest recorded version of the same; and the fact that Muslims believe their holy book is an exact account of what God revealed to Prophet Mohammad.

“They could well take us back to within a few years of the actual founding of Islam. According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet Muhammad received the revelations that form the Qur’an, the scripture of Islam, between the years AD610 and AD632, the year of his death,” Thomas said.

Even though Koranic teachings were initially held in memory or written down on various materials, including stones, palm leaves, shoulder blades of camels and parchment, Caliph Abu Bakr, the first ruler of the Muslim community after Prophet Mohammad, ordered a compilation of all the teachings. A book with everything that the Prophet had said was eventually written to the tee and finalized in form under the direction of the third leader of the Muslim community, Caliph Uthman, in AD 650.

“Muslims believe that the Qur’an they read today is the same text that was standardized under Uthman and regard it as the exact record of the revelations that were delivered to Muhammad,” Thomas said. “The tests carried out on the parchment of the Birmingham folios yield the strong probability that the animal from which it was taken was alive during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad or shortly afterwards. This means that the parts of the Qur’an that are written on this parchment can, with a degree of confidence, be dated to less than two decades after Muhammad’s death.”

Mohammad Isa Waley, senior curator at the British Library, said the latest discovery is news for every Muslim and it calls for celebration. He also explained that during ancient times, Muslims were not wealthy enough to stockpile all the animal skins necessary to make the Koran and so the text must have been written soon after the parchment was completed.

The very early dates revealed by the radiocarbon analysis could also mean that the ancient text actually predates the creation of the authorized version of the Koran. The new leaves would be available for public viewing for the first time in October this year at the university’s Barber Institute of Fine Arts. The city museum in Birmingham has also expressed interest in organizing an exhibition with the parchments later this year.

Photo Credits: Birmingham Mail